I have posted about using an R205 without a Vodafone blessed network, and I wrote a quick software inspection of the device. This time I’m writing some notes about the hardware itself.

I have originally expected to just destroy the device to try to gain access to it, but it turns out it’s actually simpler than expected to open: the back of the device is fastened through four Torx T5 screws, and then just a bit of pressure to tear the back apart from the front. No screws behind the label under the battery. I have managed to open and re-close the device without it looking much different, just a bit weathered down.

Unfortunately the first thing that becomes obvious is that the device is not designed to turn on without the battery plugged in. If you try to turn it on with just the USB connected – I tried that before disassembly, of course – the device only displays “BATTERY ERROR” and refuses to boot. This appears to be one of the errors coming from the bootloader of the board, as I can find it next to “TEMP INVALID” in the firmware strings.

Keeping the battery connected while the device is open is not possible by design. Particularly when you consider that all the interesting-looking pads are underneath the battery itself. The answer is thus to just go and solder some cables on the board and connect them to the battery — I care about my life enough not to intend to solder on the battery, that one can be connected with physical placement and tape. This is the time I had to make a call and sacrifice the device. Luckily, the answer was easy: I already have a backup device, another Vodafone Pocket WiFi, this time a R208, that my sister dismissed. Plus if I really wanted, I could get myself a newer 4G version as that’s what my SIM card supports.

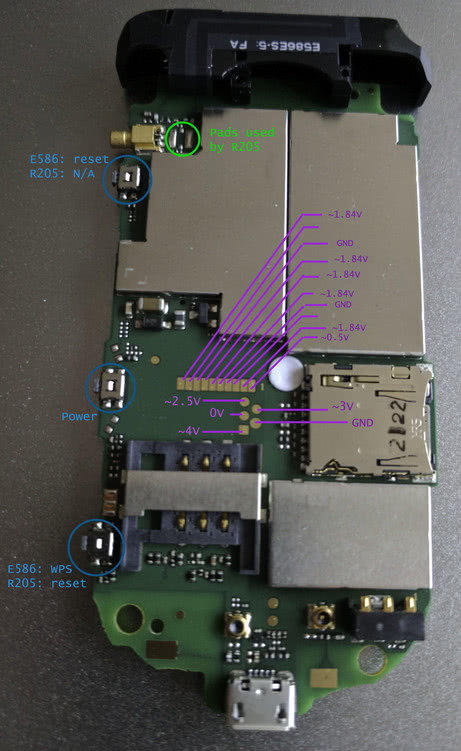

There are two sets of pads that appear promising, and so I took a look at them with a simple multimeter. The first group is a 5-pads group, in which one of them correspond to ground, two appear to idle around 3V, and one appears to idle around 4V. This is not exactly your usual configuration of a serial port, but I have not managed to get more details yet. The other group is a 10-pad group with two grounds, and a number of idling pads at 1.85V, which is significantly more consistent with JTAG, but again I have not managed to inspect it yet.

So I decided to get myself some solid core wires, and try to solder them on the five-pad configuration I saw on the board. Unfortunately the end result has been destructive, and so I had to discard the idea of getting any useful data from that board. Bummer. But, then I thought to myself that this device has to be fairly common, since Vodafone sold it anywhere from Ireland, to Italy to Australia at least. And indeed a quick look at eBay showed me a seller having, not the R205, but the Huawei E586 available for cheap. Indeed, a lot of four devices was being sold for $10 (plus €20 for postage and customs, sigh!). These were fully Huawei-branded E586 devices, with a quite different chassis and a Wind logo on them. Despite coming from New York State, this particular Wind-branded company was Canadian (now goes by Freedom Mobile); I’m not sure on the compatibility of the GSM network, but the package looked promising: four devices, but only one “complete” (battery and back cover). I bought it and it arrived just the other day.

An aside, it’s fun to note that I found just recently that Wind was used as a brand in Canada. The original brand comes from Italy, and I have been a customer of theirs for a number of years there. Indeed, my current Italian phone number is subscribed with Wind. The whole structure of co-owned brands seems to be falling apart though, with the Canadian brand gone, and with the Italian original company having been merged with Tre (Three Italy). I’m not sure on who owns what of that, but they appear to still advertise the Veon app, which matches the new name of the Russian company who owned them until now so who knows.

Opening the Wind devices is also significantly easier as it does not require as much force and does not have as many moving parts. Indeed, the whole chassis is mostly one plastic block, while the front comes away entirely. So indeed after I got home with them I opened one and looked into it, comparing it with the one I had already broken:

If you compare the two boards, you can see that on the top-right (front-facing) there is a small RF connector, which could be a Hirose U.FL or an otherwise similar connector; on the R205, this connector is on the back, making it not reachable by the user. The pad for both RF connectors are visible on as not used in the opposite board.

Next to the connector there is also a switch that is not present in the R205, which on the chassis is marked as reset. On the R205 the reset switch is towards the bottom, and there is nothing on the top side. The lower switch is marked as WPS on the chassis on the Wind device, which makes me think these are programmable somehow. I guess if I look at this deeply enough I’ll find out that these are just GPIOs for the CPU and they are just mapped differently in the firmware.

I have not managed to turn them up yet, also because I do not trust them that much. They appear to have at least the same bootloader since the BATTERY ERROR message appears on them just the same. On the other hand this gives me at least a secondary objective I can look into: if I can figure out how to extract the firmware from the resources of the update binary provided by Vodafone, and how the firmware upgrade process works, I should be able to flash a copy of the Vodafone firmware onto the Wind device as well, since they have the same board. And that would be a good starting point for it.

Having already ruined one of the boards also allows me to open up the RF shielding that is omnipresent on those boards and is hiding every detail, and it would be an interesting thing to document, and would allow to figure out if there is any chance of using OpenWRT or LEDE on it. I guess I’ll follow up with more details of the pictures, and more details of the software.